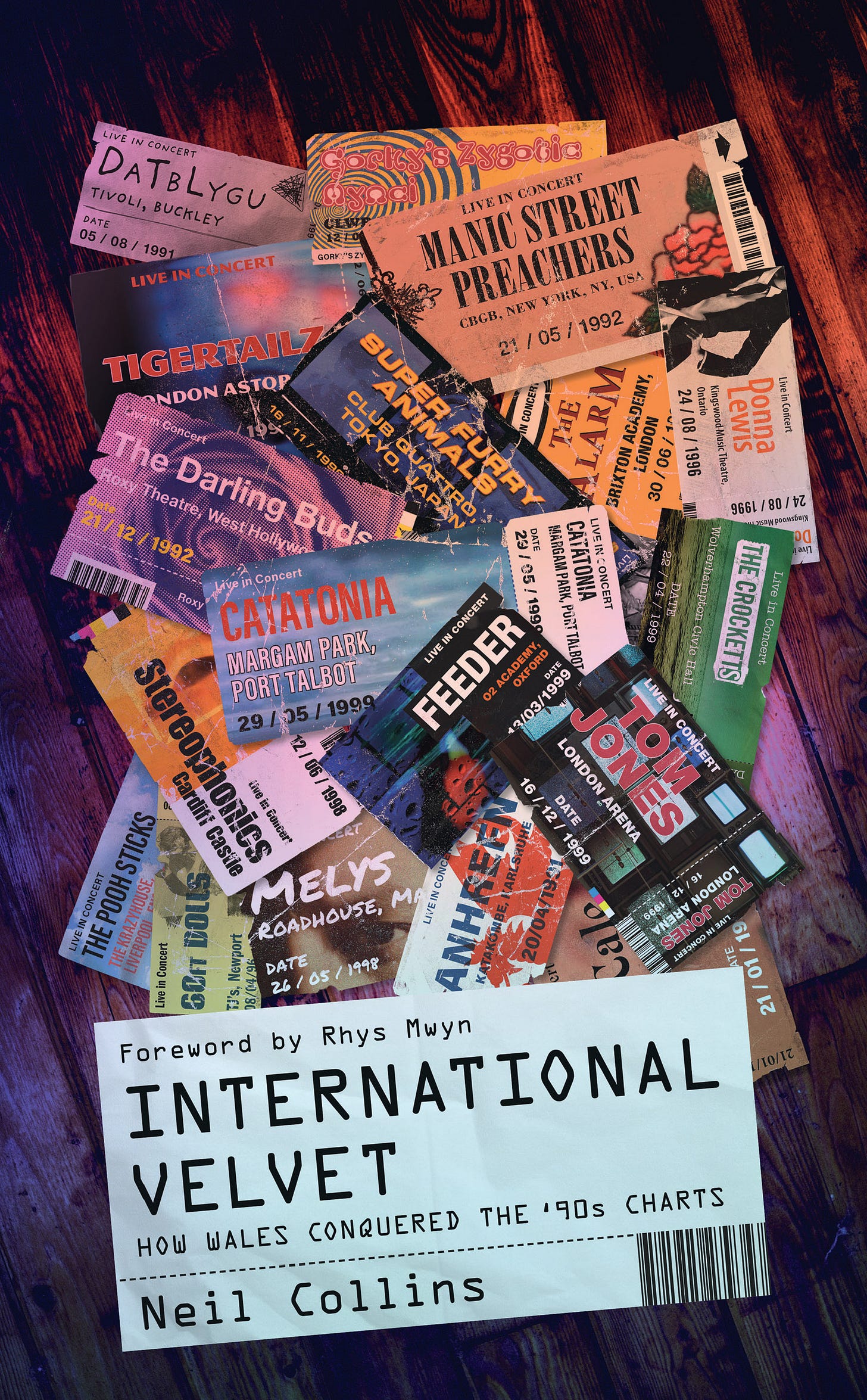

The Write Hear Interview: Neil Collins and 'International Velvet - How Wales Conquered the '90s Charts'

"The success stories aren’t quite so much anomalies now as they were before the ‘90s."

In the tapestry of musical history, there are moments where the unexpected threads weave a pattern of brilliance. Neil Collins' International Velvet: How Wales Conquered the '90s Charts is a celebration of such a moment. A testament to the raw talent, fierce spirit, and sheer audacity that propelled a wave of Welsh musicians, including Manic Street Preachers, Stereophonics, Catatonia and Super Furry Animals onto the global stage. It's a story of underdogs and outsiders, of dreams defying the odds, and of the enduring power of music to ignite the human soul.

On a Zoom call from his home in Bridgend, 20 miles north of Cardiff, Collins examines the cultural and socio-political factors that contributed to this musical phenomenon, known as Cool Cymru, and how it helped to reshape Wales' national identity.

I am not kidding you, Neil, my head is exploding over this book. It is so thorough in not only explaining but also celebrating music from Wales. There's a distinct flavor to this that helps a lot of people because at least for the general American viewpoint, it's hard to pinpoint Welsh music. How do we bridge this gap?

I think it is something that's changing a lot in terms of if you were to go over to America, maybe before the ‘90s, even in the ‘90s, a lot of responses when you say you're from Wales, Americans would say, “Oh, Wales, London” or “Wales, England.” They would think it's the same thing! So I think there's been that healthy influx of Welsh music from the ‘90s.

You know, the Manics toured with Suede in 2022 in America. You've got some bands that seem to just fit better in America. There's a band called The Joy Formidable. They're from up in North Wales, but they have a sound that's akin to Smashing Pumpkins. That sort of alt-rock sound. They seem to fit in better over in the States. Then there's acts like Donna Lewis. “I Love You Always Forever,” which was a Number 2 hit on the U.S. Billboard charts in 1996 and Bonnie Tyler’s “Total Eclipse of the Heart."

Bonnie Tyler - Total Eclipse of the Heart (Turn Around)/℗©Round Hill Music/YouTube

I started writing the book through the Welsh Music Podcast which I started five years ago with a friend and former colleague [James Cuff] that celebrates the past, present, and future of Welsh music. We found on our social media platforms that the band that seem to inspire the most interest to Welsh artists are The Alarm. There's been a lot of their recognition in the States, but before them, Badfinger was pretty big in the States. Although it's a really sad story in terms of they should have been absolutely huge.

Wales was seen as a bit of a laughingstock in the late ’80s, early ‘90s. We still have moments you can point to and think, “You know, what about Badfinger? They were a brilliant band! Or what about [heavy metal band] Budgie?” In the ‘80s we had four mega-selling artists who had commercial acclaim. There's Tom Jones, Shirley Bassey, Bonnie Tyler and Shakin’ Stevens, who was the highest UK-selling artist in the ‘80s. What happened in terms of alternative music, there wasn't a lot that was going on in the ‘80s.

If you look at a lot of Manics’ early coverage, it's all clunky cliches about their Welshness, and that persisted until the mid-’90s when the Cool Cymru tagline proved Wales was of worth. The success of the ‘90s has got a hell of a lot to thank the Welsh language scene of the mid ’80s. There's two bands in particular, Y Cyrff and Ffa Coffi Pawb. One was Gruff Rhys' band, the other was Mark Roberts. They go into the ‘90s, shift members around and form Super Furry Animals and Catatonia, two of the greatest Welsh bands ever but also two brilliant bands from the era, full stop, from the UK, in the ‘90s.

Ffa Coffi Pawb - Sega Segur/℗©Sub Pop Publishing/YouTube

Were you supposed to be celebrating your Welshness? It seemed like a lot of bands didn't want to be associated with Wales.

Some bands were traveling over the Severn Bridge to Bristol to get an English postmark on their record so that it wasn't just chucked away! I spoke to the record producer of the Super Furry Animals, Gorwel Owen, who said that there were quite a few bands he produced in North Wales who would play on the idea they were from Liverpool which is 20, 30 miles up the road, just to get more recognition. So yeah, there was a real problem of A&R men crossing over the Severn Bridge to come and check out bands in Wales. They were few and far between. I interviewed the Manics producer Greg Haver for the book, and he said they practically threw up the bunting if there was an A&R man spotted in Wales at the time. We're only a country of three million, so there was a limited amount of what we could do from the inside.

I interviewed [the Manic Street Preachers] Richey Edwards at the end of 1991. I knew about the ‘4 real’ incident’ when he carved that into his arm during an NME interview in May. When I talked to him, Generation Terrorists had not come out. But he felt grateful that there was attention because this is what they had been looking for all those years. We didn't touch so much on Welsh this and Welsh that, but knowing that they were from Wales, I asked would they go back and play there. He goes, “We played one gig and that was it.” And I said, “So you're never going back to Wales to play?” And he said, “No. Never. All of our teenage years were spent in James' bedroom, watching TV and videos and reading anything we could get our hands on. We never ever thought about Wales at all. It's like we're in this town and it's shit. It meant nothing to us. We wanted to leave.” What are your thoughts on that?

I think what you see with the Manics is more a testament to their youth. When you're young, you want to get away from where you come from. You saw the same with Oasis in a way. It was grey, old Manchester. But they came to accept that. With the Manics, they come from the South Wales Valleys, which has always been a bedrock for heavy music. There's a bit in the book where I write it’s like the clanging of machinery all week reflects the working week, and then on the weekends, they're clanging away on other stuff, which is instruments. So if you look at the Manics’ early influences, there's a lot of American FM rock on there. They famously wanted to outsell Guns and Roses’ Appetite for Destruction which sold 16 million copies. I think there's nothing on that first album that would make you think they're Welsh. From the cover, they look like Mötley Crüe!

In the early days, the Manics had a lot of their coverage in Kerrang! and Raw. At the start, they wanted to emulate their American heroes. You can't detect any sort of Welsh accent in James Dean Bradfield’s singing voice. Certainly by 1996 when Everything Must Go came out, they've got much critical acclaim that they can go back and embrace their Welshness: Nicky Wire with the Welsh flag on the amp, which has persisted all the way until now. So it's one of those things, I think. When they came out in 1991, ‘92, and were flying the Welsh flag, they would have been ridiculed even more than other Welsh bands. They had to put up with a lot of flak because they were the sacrificial lambs for what followed. But if you look at their work from 1996 onwards you've got This Is My Truth, Tell Me Yours, which was a Number One hit, a 5 million-selling album that is absolutely strewn with Welsh references. It's named after an Aneurin Bevan quote on forming the NHS. The cover is on a beach in Porthmadog in North Wales. There's references to R.S. Thomas, the poet, on “Ready for Drowning.” That's about the flooding of a Welsh village in North Wales to supply Liverpool with water. There's the reckless Welsh nature which you see in people like Richard Burton, Rachel Roberts and Dylan Thomas, where they kind of drank themselves to death. You've also got “If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next,” about the Spanish Civil War. That was about people joining the international brigades to fight fascism.

Manic Street Preachers - If You Tolerate This, Your Children Will Be Next/℗© BMG Rights Management (UK) Limited/YouTube

There’s a sense of hiraeth, as they call it in Wales, which is like a yearning homesickness. And you also get another Welsh term called hwyl, which is about guster, on songs like “Design For Life,” that sort of ‘throw in the kitchen sink.’ In 2013 they released a sister album of sorts to This Is My Truth, Tell Me Yours called Rewind the Film, which is a collection of earthy Welsh folk songs. On that, they have a song called “Show Me the Wonder” which said, “We may write in English/

But our truth lays in Wales.” It's like they've never written in the Welsh language, but that's not to say that they're not proud of their Welshness at all.

That harks back to what Richey was saying in terms of they couldn't be anything in the early ‘90s. They couldn't come out and say they were really proud of their Welshness because it was used as a stick to beat them with. Nicky Wire says that they were born in a shithole in terms of where they lived. But it's our shithole! They had a fierce gang mentality of defense against anyone else taking the mick out of it. They were allowed to be themselves. There was a time of mass frustration, whether it was Thatcherism or the [1984-85] miner’s strike, that produced great art. The Manics are a great sort of mishmash of all those influences and also inadvertently, their punky anger and their great records all came out after Thatcherism.

Manic Street Preachers, November 1994. Left to right: Sean Moore, Nicky Wire, Richey Edwards, James Dean Bradfield.

You touched on the fact that the Manics would be considered at the time, more of a hair metal band but with a Bowie thing going with the eyeliner and the clothes. Moving along, they became more connected in being able to speak out politically as well. Is that why they haven't made a dent in the States? There's no universal lyrical connection from what I hear.

I think it’s the fact that they come from a tiny place. Although it's an amazing story in terms of these four kids from a working-class mining village went to take on the world. I do tend to think they haven't got that sort of huge sound of say, U2 or a frontman like Bono, who will just be ubiquitous in terms of talking about different things, and put himself in that position.

They went quiet, certainly after the disappearance of Richey. I don't think conquering America was ever on their radar after that. I mean, in February, 1995, they were due to go out for a promotional tour of the U.S. and that was when Richey disappeared from the Embassy Hotel. But It's understandable in a way. [Newport band] Feeder toured the States for nine months in 1998. But the States are massive, as well you know. It's not like a tour in the UK. You can pretty much drive from one end of the UK to the other in a day.

Conquering America is a hugely difficult thing. Oasis never really quite managed it, I would say. U2 and Coldplay have. They've got those commercial-sounding songs that relate across the board. I think the Manics are more niche in terms of references, like [A Design For Life’s] “Libraries gave us power” which, although the fans absolutely love, perhaps it doesn't quite register to the wider consciousness. But I think it makes them more of an interesting band.

You could easily write an encyclopedia on the Manics in terms of all their different references. The quotes they put on their setlist. The Manics and the Super Furry Animals are the real generational talents of that era.

Now here's the interesting thing. You can discover all of that because of the internet. Before that, you had to be tenacious about wanting to find that music. However, a band like Gorky's Zygotic Mynci, I knew nothing about until I read your book. This band is totally amazing, and they don't exist anymore! During the time that I was covering that scene, there were a lot of shoegaze bands: Chapterhouse, Slowdive, Ride and Swervedriver. It feels like Gorky’s could have fit in there.

Yeah, yeah, absolutely.

Why did they not happen in America?

They didn't fully take off in the UK either. They never had a top 40 hit in the UK. The closest they ever got was “Patio Song,” which agonizingly got to Number 41! But I think they always reveled in their outside-ness. I think they quite liked that position. It's a strange one, in a way, because the Super Furries have got that madcap genius, more of a pop-rock template. It's more accessible. People will buy it and it gets into the charts easier. If you look at Gorky’s influences, there was a lot of prog rock and old, obscure records. Stuff like Captain Beefheart and being influenced by Kevin Ayers of Soft Machine. But it's a lot more like indulgent music. I certainly think that they were a buried treasure of the whole era, really. They were only about 14, 15 when they started. If you listen to their records, on the end, they've purposely left in arguments with their parents because of the noise that they were making!

Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci - Patio Song (Later…With Jools Holland 1997)/℗©Euros Childs/YouTube

On their third album Bwyd Time, which means ‘food time’ in Welsh, it's very, very psychedelic. And on the sleeve, they're in wizard garbs; they're aesthetically amazing to look at. Alan Holmes, who was one of their affiliates, did all their artwork. There's a real sense of magic to it all by the time they come to the fourth album Barrafundle in 1997. They're trying to get into a more mainstream audience then. The Welsh songs become a little bit more of a minority. It's a trajectory, like with Catatonia and Super Furries. Once they get assigned to the major labels, the English language is predominant. It's a real shame that they didn't quite break into the mainstream. They've always been critically acclaimed. In terms of Stereophonics, who are quite a solid group, but they’re a bit formulaic. I think there was a lot more creativity and eccentricity with Gorky’s.

Over here, Stereophonics are still on the fringe, although I know of Kelly Jones. Did they downplay their Welshness? Whereas bands like the Manics, after a while, started to celebrate it.

By 1999, when Stereophonics became big, the perception of Wales had changed to the extent that even their hometown, which was this tiny little mining village, one road in and one road out called Cwmaman, had come to the national consciousness through the band. They were fiercely loyal to their roots. Anyone up there, if you asked where you were from would say, “I'm from Aberdare,” because it's the nearest big town. But Stereophonics never did. It was always “I'm from Cwmaman.” But it's a very sort of Welsh thing that you'll often see in Wales football games, when they're played abroad, they'll have flags in the crowd and they'll always have the tiniest, tiniest town written on the flag. Welsh people are sort of parochial that way. What you saw with Stereophonics was their first album [1997’s Word Gets Around] was fascinating because it's true life tales of their hometown.

Stereophonics - A Thousand Trees (Official Video)/℗©Universal Music Publishing Group/YouTube

When I was a journalist years ago, I actually worked for the local paper for a couple of years. A lot of the people mentioned in their songs are still walking around the town. The song “A Thousand Trees” was about a scandal where a teacher had allegedly got caught with their pupil and went to prison. When he came out, half of the town believed him and half didn't. So that guy was still walking around the town by the time I had gone to work there.

This sounds like an episode of Broadchurch!

Oh, it does! And then there's songs on there like “Local Boy in the Photograph.” It’s about a friend of a friend of Kelly's who asked him for the train times and then threw himself in front of one of the trains. I think they did have a tiny bit of a bad rap because they were writing about real-life people. I know with “Billy Davy’s Daughter" which is about another suicide, they approached the father in the pub to say, “Should we change the name of the person?” So what you found then with Stereophonics was that they couldn't write like that once they become stars. I liken it to Oasis with “Rock ‘N’ Roll Star.“ That song could only ever be the first song on their first album, because it's the dreams of being a rock star, you know, with your tennis rackets, strumming in your bedroom.

Stereophonics, March 1997. Left to right: Stuart Cable, Richard Jones, Kelly Jones.

By the time they reached their second album, it's a bit more of a formulaic songwriting because Kelly was writing a program for BBC when he got signed. Then they went into more generic rock and roll. In terms of Cool Cymru, they are of their place and time, and they certainly contributed to the growing confidence of Wales in the ‘90s.

Another band that should have been supersonically huge was Catatonia. Was that again sort of like a parochial or nationalism thing and why didn't that transfer to the States? To me, their feel is hard and edgy like the Manics.

What I think happened with Catatonia, what hamstrung them was they were constantly having quarrels with Warner Brothers in America. They had amazing songs that related to universal truths of life. Great choruses. Their guitars are very Britpopesque as well. They had everything sort of set up for them to be big in America, with the glamorous front woman [Cerys Matthews] as well.

Catatonia - You’ve Got A Lot To Answer For [HD 1440p 60fps]/℗©Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC/YouTube

Catatonia was signed to Blanco y Negro, which is a subsidiary of Warner Brothers. It's run by Geoff Travis in the UK, who also runs Rough Trade. There was so much quarreling with the US label and it was sometimes stupid stuff. In America, they didn't release their singles for a long time. They kept pushing back the release of International Velvet and “Mulder and Scully” in America, which should have been huge, just based on how massively popular the X-Files were.

The arc in the book is from a country that was ignored and derided to a country where Cerys Matthews is singing every day “I thank the Lord I’m Welsh.”

Where it becomes odd with Warner Brothers is that they seem to want to be too clever for their own good. If you think you really need to ride on the coattails of the popularity of the show, you expect the promo video to be very sort of like – you've either got Gillian Anderson or David Duchovny in the video or you've got lookalikes. Now, the British promo video did have that. So you had Mulder and Scully in TJ's, the venue in Newport, Wales. The video also starred Reese Evans, who became a Hollywood movie star afterward.

Catatonia - Mulder and Scully/℗©Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC/YouTube

Now the US label insisted on the video being reshot with no reference to Mulder and Scully. So instead, it's Cerys running away from a city full of sentient filing cabinets. It just doesn't make any sense. After a while, the band just got fed up with the American label. With that as well, Catatonia was a very fractious group, anyway. What was kept quiet in the early years, was that Cerys and Mark were an item. They were a songwriting partnership and a real-life partnership. But that broke down and was very sort of, acrimonious. The band was teetering on the edge all the time, and they were probably lucky to get four albums in the end. I suppose their main sort of worry day-to-day was, will the band stay together more than conquer the American dream?

Noel Gallagher would say later, “If it weren't for Richey, then I wouldn't have gotten where I am.” Would you be looking at it in a regional sense, where you would have admiration for people in Wales, because they were metaphorically being looked down upon and they rose up to give more of an incentive to others?

The arc in the book is from a country that was ignored and derided to a country where Cerys Matthews is singing every day “I thank the Lord I’m Welsh.” Singing that full stop is such a shift in confidence. She wouldn't have been singing that at the start of the decade. So although it's a great story in terms of it's a tiny nation that's turned its fortunes around, I suppose people in England may not see it like that. They may think of it as “We weren't being so harsh” or kind of like apathy “Well, who cares?” With Britpop, you've got five great bands at the top, which I would say were Oasis, Blur, Pulp, Supergrass, and Suede. With that, you've also got third rates or copyists. It's a bit bland. It's kind of trying to recreate the Swinging Sixties all the time.

With Britpop, you would have bands like Garbage and Placebo who only had one British member. It became this beast that went completely out of control. Bands were getting sucked up into the Britpop bubble that weren't Britpop at all.

Was it a convenient tag for the British music press?

Yeah. You’ve got a lot of misogyny as well. I highlighted a few passages in the book, where if it's a female-fronted band, quite often the reviews would be mentioning the female singer before any sort of music's analyzed. I don't think you quite got that with Cool Cymru. It's that huge shift in confidence from the start of the decade, where you had bands sort of hide their Welshness to seven or eight years later, bands wearing their national identity on their sleeve: “I'm proud to be Welsh,” which is incredible, really.

How do you see the growing-up period in today's music scene in Wales? It seems like there's been more of a pushback to understand the Welsh language. Is the government requesting kids now to learn Welsh as part of their schooling?

A big change in Wales was the introduction of the Welsh Language Act in 1993. When I was in school it was about a half hour a day of Welsh. That made a big difference, and I think by 2050 they want to have a million speakers in Welsh. What I think is really healthy in Wales now is, you get so much more interest in Cymru from non-Welsh speakers as well. Catatonia, Super Furries and Gorky's made a big difference in bringing it more to the fore, but if you went back to the mid ’80s where you see in bands like Datblygu and Ffa Coffi Pawb, that audience is predominantly Welsh-language speaking.

You get bands like Adwaith now, who are an all-girl group, who won the Welsh Music Prize with both their albums [2018’s Melyn and 2022’s Bato Mato] and they get national acclaim. So The Guardian would review them, and The Independent have reviewed them, whereas maybe 10, 15 years ago, you wouldn't have had a small Welsh-language group being reviewed nationally like that.

Wikitongues: Hywel speaking Welsh/©Wikitongues/Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license/YouTube

And there’s Welsh language festivals. We had one called Tafwyl recently, that attracted about 40,000 over the weekend. So yeah, it's a healthy place in terms of you're not selling anywhere near the same levels of units as years ago, but there's definitely a more diverse scene. Young artists in Wales don't have the complex of battling with the clunky headlines. They're just considered on their merits rather than their nationality.

With the internet, this is how I was able to find all the music I missed and that feels like a good thing, because that means I can get myself past all of that sort of divisiveness. But also a book like yours is highly valuable to me from a scholarly and academic point of view. As a fan of Michael Sheen, by the things that he's done in the past couple of years – coming back to Wales, living in Port Talbot and also supporting the Manics by having them in the production he did of The Passion – have helped. But how much weight does the music press in the UK hold over bands nowadays?

The music weeklies have completely gone in the UK now. When I say Wales has always fought above their weight musically, it's not just that. It's in terms of actors and stuff. In Port Talbot, you've got Richard Burton, Anthony Hopkins and Michael Sheen all from the same town. Which is incredible. But in terms of how Wales is seen now, there is a lot more respectful perception than it was years ago. I think there is a lot more recognition of what Wales has given the world, certainly with the new artists coming through now. There's Gwenno, who was nominated for the Mercury Prize. You've got Skindred, who were the first Welsh band to win a MOBO Award earlier this year. The success stories aren’t quite so much anomalies now as they were before the ‘90s. They say Wales is the land of song, which again is a little bit of a backlash. There's a quote in the book where it says that the land of song was bestowed on Wales by the Victorians. So although it's considered a flattering thing, you've still got that “Well, we didn't call ourselves that!” But I do think there is something in the water in Wales. We've left quite an imprint, I think.