The 'Alternating Currents' Legacy Interview: Don Henley

In 1992, An Eagle Takes Time To Save Walden Woods

Prologue

He rounded this water with his hand, deepened and clarified it in his thought, and in his will bequeathed it to Concord. I see by it’s face that it is visited by the same reflection; and I can almost say, Walden, is it you?

Walden, Henry David Thoreau

It seems the never-ending question “Why?” is posed more often than not to musician Don Henley these days. Not that he doesn't have an answer. In fact, he has many answers and explanations. However, the real question should be “When?”

When is now and the subject in question is Walden Woods. The fight to save the acres of Concord land that Henry David Thoreau called home has been at the center of Henley's life for the past two years. Since founding The Walden Woods Project in April 1990, the ex-Eagle has been a one-man publicity tornado and crusader in raising awareness of Thoreau and the impending destruction of the land that served as the subject for the author's most famous work, Walden. The general consensus was that Henley must have been out of his mind to attempt such a daunting feat. But, “That's okay,” Henley said. “I've heard that before.”

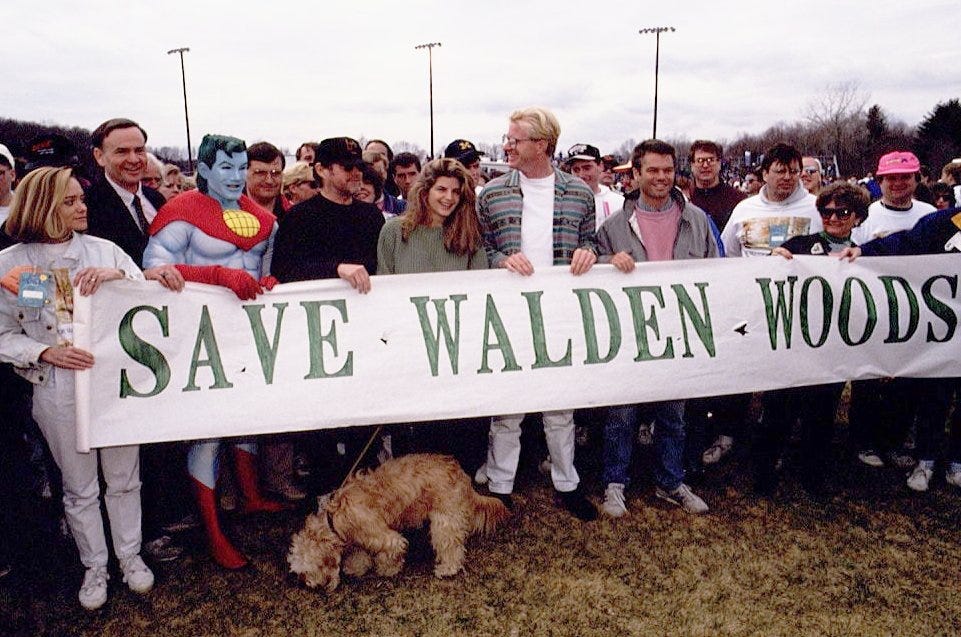

Sitting in a suite at the Boston Harbor Hotel, the opulent surroundings were a marked contrast to Henley’s casual attire of jeans jacket, black T-shirt, black jeans, and cowboy boots. Having flown into Boston to participate in a walkathon to raise money for the Project, the 44-year-old bearded Henley was articulate and thought-provoking on the subject.

“Don Henley led more than 6000 folks on a 6-mile walk to save from commercial development, the woods around Walden Pond in Concord, MA.” April 12, 1992. Photo: Brooks Kraft LLC/Sygma via Getty Images

“Thoreauians have always met with opposition and have been looked at as scants and misunderstood. As was Thoreau himself. He was looked at as a crackpot. But great thinkers often are. They thought Van Gogh was a crackpot, too. Jesus and Gandhi and everybody else like that.”

It’s a credit that Henley has stayed the course in the face of opposition, dealing with the stigma of being ‘a rock star from California.’ “In the press conference [at the Hard Rock Cafe] today,” he commented, “Some guy said, ‘You live in Hollywood.’ I don't, by the way. I live in Los Angeles. He said, ‘What has this got to do with you? Why are you so interested, being way out there?’ It’s a very small world, the way I see it. It's not ‘way out there.’ What we do in one part of the world has consequences in another.”

The fight has been — and continues to be — a complicated, complex web of negative publicity, heroism, and politics. The Project has been successful in raising enough money so far to purchase land at Bear Garden Hill, Fair Haven Hill (from developer Philip DeNormandie), and recently the 16-room DeBlois House. But this is only the tip of the iceberg. There are 2,680 acres of land designated as Walden Woods, and Henley is adamant about the protection and preservation aspect of the Project and the legacy left by Thoreau’s writings about Walden.

Bear Garden Hill, Concord, MA. Photo: The Walden Woods Project

“In this country, we’re very good at preserving memorials to violence. We’re a violent society. Arnold Schwarzenegger and Steven Segal and Sylvester Stallone have proven that time and again at the box office. So it’s ironic we can’t preserve a place where man tried to establish harmony with nature and with his fellow man. And that to me is the sad part of the whole thing.”

The political angles are also fodder for the Walden campaign. The initial publicity battle began with developer Mort Zuckerman and his company, Boston Properties, proposing an office and condominium complex just yards from Walden Pond, long thought to be immune from modern-day intrusions. This was the starting gun for Henley in 1990. But now that the Project has helped acquire 60 percent of the 2,680 acres, Zuckerman, bowing to the growing public pressure and publicity, has sold off his interest and is not the threat he used to be. “However,” Henley cautioned, “Mort is still chairman of Boston Properties, so he’s not completely removed from the project.”

In dealing with Zuckerman’s partner, Henley noted that The Trust For Public Land — the organization keeping the key lot, Brister’s Hill, off the market — and Boston Properties have been negotiating “for eighteen months and I think the price has come down some” Henley asserted. “But I don’t think it’s the responsibility of a non-profit land preservation organization to reimburse a developer for cost overruns for what was basically a bad business deal. We owe it to our contributors not to pay an exorbitant price for this land.”

Although property costs have gone up because of stalling and the recession, Henley is hopeful that the estimated $8.3 million can be raised and added that the town of Concord didn’t renew Boston Properties’ land permits, which expire June 1. Good news for now.

Brister’s Hill, Concord, MA. Photo: The Walden Woods Project

It’s interesting to note that through all of the hoopla, the negotiations, and the music, Henley’s initial love of Thoreau and his real reasons for taking up the Walden banner are a quiet side story. It’s easy to get caught up in the facts and figures at hand, but when questioned on whether he and Thoreau were destined for one another, Henley laughed.

“Oh, gosh! I don't want to go that far. How and where I grew up had a lot to do with it. I grew up in the woods and the woods took on a certain spirituality for me that replaced organized religion.

“I was a member of the First Baptist Church in Linden, Texas and we had a preacher who scared me, ‘cause he would yell and preach hellfire and brimstone. So I was looking for something else.”

Henley — an only child — later found his “spiritual awakening” through a combination of personal tragedies and the distance of college studies at North Texas University.

“I believe I was 21 or 22 and I went back and rediscovered my hometown. And my father was very ill. He was dying of heart disease. I’d seen a lot of death in my family. My grandparents had died. My aunts and uncles and a couple of my close friends had died.

“So, my father became ill and I started asking the big questions. Y’know, who are we, where did we come from, where are we going, why are we here? And I found those answers in the works of Thoreau and Emerson in the woods surrounding my little town in Texas. It really helped give me an anchor on that windy sea of doubt when my father was so ill and suffering so badly.”

Henley’s interest in English was by no means the traditional college method. He just took what he liked. “I didn't care whether I got a degree in this or that or what the counselor said I was qualified for. People would ask, ‘What are you majoring in?’ I would say, ‘English Lit.’ They’d say [assumes highbrow tone] ‘Oh, you’re going to be a teacher?’ And I’d say, ‘No, I just Iike it!’”

He then related a telling story from those days in what he now considers a turning point in his life. “I had a freshman English teacher who was great. He was a bohemian Italian. Had long hair — this was in the fall of ‘65 — and I’d never seen anybody like him. He had hitchhiked all over Europe and he came into class — actually this was the first college I went to, which was Stephen F. Austin University. A real redneck, little animal husbandry, ROTC-kind-of-school in east Texas. I went there for two years.” Henley stopped and smiled wide. “My hair touched the top of my ears and I got beat up for it constantly.

“Anyway, this teacher came in with a big, polka-dot, puffy-sleeved shirt and pointy Italian boots on and sat in the lotus position on top of his desk. First day of class, we were kind of going, ‘Wow!’ He looked around the room and said [sighs heavily] ‘I know what the problem is. You’re all here because your parents want you to be something. And your counselors want you to be something and told you to make something of yourself. They want you to be like everybody else.’ He said, ‘Look around the room.’ We all looked at each other. He said, ‘Do you really want to be like everybody else?’” Here Henley paused and laughed at the memory.

“He said, ‘It’s very important that you understand that you shouldn’t succumb to the pressure to be what they think you ought to be. If it takes you the rest of your life — if it takes you until you’re 50 or 60 years old to decide what it is you really want to be — then you wait. You take that time.’” Henley finished his tale. “And that made a big impression on me.”

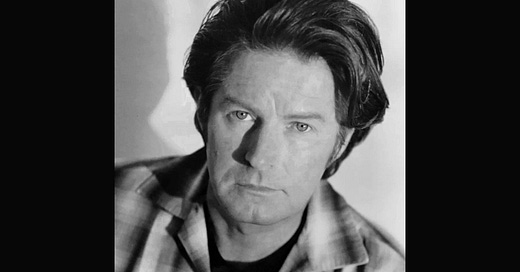

A young Don Henley, circa late 1960s.

To many it now looks as if Henley is light-years removed from those small-town roots and lives the life of a successful and well-traveled rock star. How does he see the connection now after all these years?

“Well, in my mind and in my heart, I’ve stayed where I was,” he answered. “California is only a place that I went because it was the hub of the music industry. That was the pilgrimage I had to make in order to get the message across. My heart stayed right there in Texas and Thoreau’s philosophy stayed right with me and guided me all my years in California. I slipped off the path a few times, because it’s easy to do out there. But I’ve come back — I’ve come full circle. I’ve just bought a place in Dallas, come back to Thoreau and come back East. So, in a way, it’s a circular journey. As life often is.”

It may appear that in print, Henley comes off very serious and somber in his attitude on life, and, granted, The Walden Woods Project is a serious undertaking. But as for humor? “My life is full of humor,” he responded. “I have a dry, sick, dark sense of humor. It’s a serious subject, but it’s also about beauty, ultimately. Which is what nature represents in its ultimate form.”

Henley also has a personal stake in other parcels of land and water that are currently threatened by development. Caddo Lake, just a short drive from his Texas hometown, was under siege from the U.S. Army Corps. of Engineers, who wanted to build a canal through the lake.

“It was just saved by the Texas Nature Conservancy,” Henley said enthusiastically, “‘cause they bought up 7,000 acres.” Research showed the lake — created by natural disasters — was privately owned. The Conservancy bought up the land and can now keep the Engineers out. “It’s great and I’m so relieved,” Henley said. “I’m gonna go down there and go fishing. It’s where I caught my first fish. That’s my Walden.” He's also involved in preservation work out in Los Angeles and Aspen, Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley.

He’ll be taking somewhat of a breather from The Walden Woods Project after his return home — “Just give me a week or two and I'll be fine” — and start back to work recording a follow-up to his Grammy-winning 1989 release The End Of The Innocence. He may try to organize some concerts later on in the fall here in Boston and has actually asked Aerosmith if they will do a show specifically for the Project. But that doesn't mean it's over for him and his personal involvement.

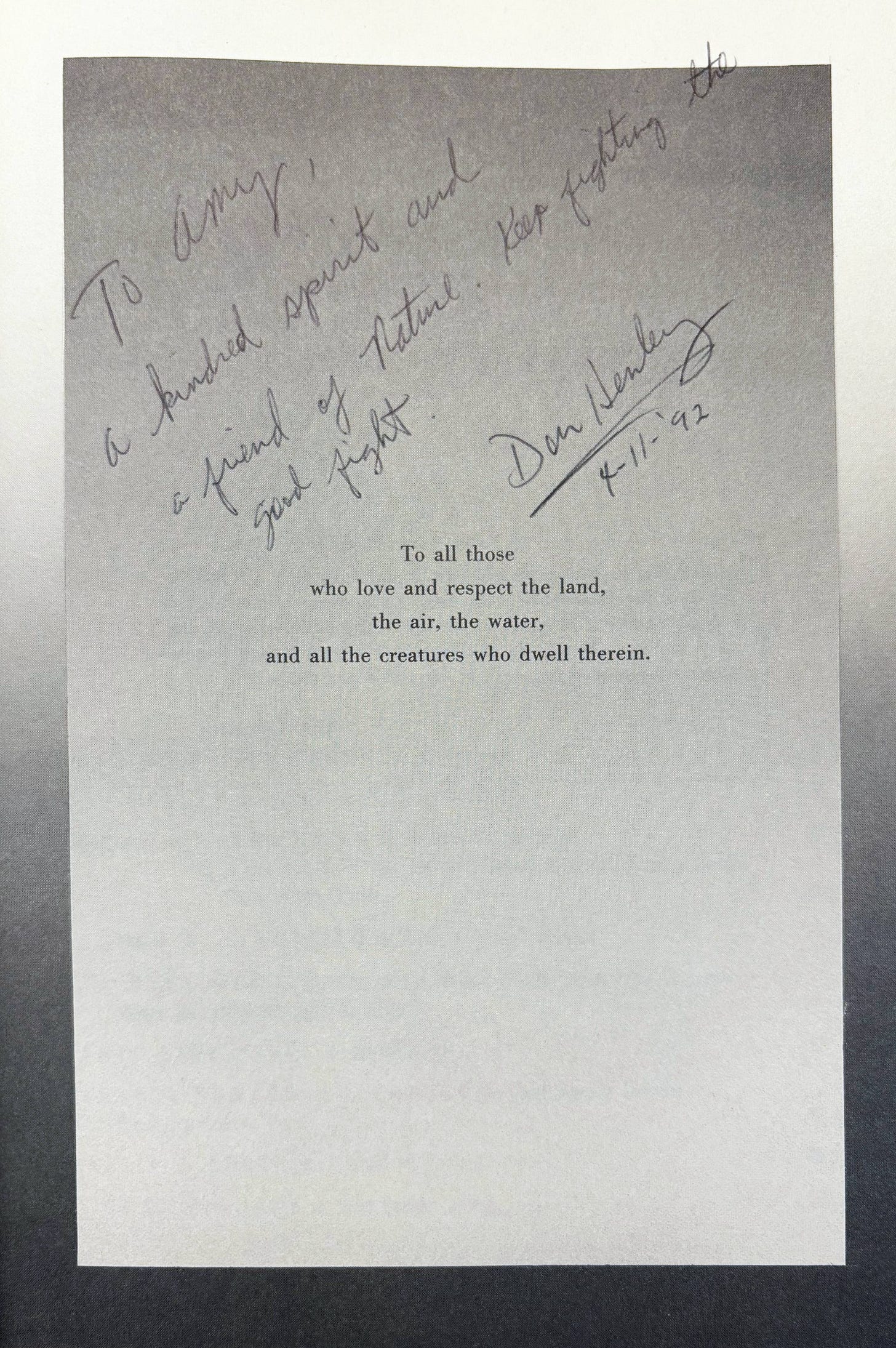

“I'm very grateful for the success we've had. This thing is a household word now. It’s everywhere. I just don’t want to wear out my welcome. If somebody would give me eight million bucks, I’d go away. But until I get another eight million bucks, I’m just gonna keep on doing this until it’s done. We’re not going to quit.” He gives generous praise to Kathi Anderson, Executive Director of The Walden Woods Project, and Ed Schofield, president of The Thoreau Society. And also his friends way out there in Hollywood.

“They are there when you need them,” he offered. “I will stand up for them anytime. They are knowledgeable, hardworking, sincere, and committed. And I couldn't have done this without them.”

Clearly, Henley is doing this for future generations, in the hopes that with a little nudge from himself and his peers, they will come to appreciate the values that Thoreau strove for. Henley, though not prompted, feels the close kinship with those simpler times and simpler values.

“I’m not doing this to be remembered. I’m doing this so Thoreau and his principles will be remembered. And I think in this country, we need to listen more closely to the wisdom of voices from the past and maybe we would not keep making the same mistakes over and over again.

“I've learned through personal experience that “stuff” does not make you happy. You spend your whole life acquiring “stuff” and then you die. So, that's why I love Thoreau and I love that quote: ‘I went into the woods to live deliberately. To front only the essential facts of life and see if I could not learn what it had to teach and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.’

“So I say, ‘carpe diem.’ But carpe diem with an eye towards the past and an eye toward the future.”

wow, what a beautiful piece of writing.

I made my pilgrimage to Walden a few years ago, having long had an intellectual crush on Thoreau. (I moved to New England due to that crush actually). Walden is sacred ground, no quetsion.

For me, the most powerful message of Walden is that it's a testament to the power of writing. There are thousands of ponds just like Walden throughout New England. Were it not for one man deciding to write about his, Walden would just be another one of them.