Book Review – 'Washita Love Child: The Rise of Indigenous Rock Star Jesse Ed Davis'

"Jesse Ed Davis is resurrected in story" — Joy Harjo

Jesse Ed Davis. An Indigenous touchstone who played like the rock star he wanted to be.

In Douglas Kent Miller’s Washita Love Child: The Rise of Indigenous Rock Star Jesse Ed Davis, we’re reminded that Davis — who passed in 1988 — was a soul dedicated to his craft, built on the foundation of his Native Oklahoma ancestors.

In the 21st century, Davis is not so much a name as a sound and even then, you might not recognize his style. He had none. He was his own being. Someone who came in like few in that era could, lift a song, and have you point a finger later to say, “Aha!” in tandem with “Who the hell was that?”

Jackson Browne’s 1972 “Doctor My Eyes.” That’s Davis on guitar, including the unforgettable solos sprinkled throughout. George Harrison’s 1971 The Concert for Bangladesh: Davis was there onstage. John Lennon’s underrated 1974 release Walls and Bridges is Davis at his most sublime and subversive. He played with Taj Mahal, The Faces, Bob Dylan, and Leonard Cohen.

Jackson Browne — Doctor My Eyes/℗© Criterion Music Corp., Open Window Music/YouTube

He could be a contradiction in terms, known for his virtuoso playing, yet plagued with self-doubt and insecurity. Born in Oklahoma in 1944, he aspired like every boy his age to be creative, whilst be recognized beyond the deep Indigenous genes. Yet no one could see that his Native American heritage — Kiowa, Comanche, Cheyenne, Mvskoke, and Seminole ancestors — were ingrained within his DNA.

What Miller emphasizes is not that Davis is trumpeted as an Indigenous figurehead during his early years when such a position could have been possible. Instead, he stresses his abilities as a musician that transcended levels of hierarchy and depth of self. He simply was as Miller writes, “more of an interlocutor than a Red Power activist.” Or, as some people like Bonnie Raitt would say, he was a “badass.”

Miller provides an intense dive into Davis’ ancestors and the history of his paternal great-great-grandfather Tah-pui, sub-chief of the Yappaituka band of Comanche people, and his maternal great-grandfather Gui-Pola, a Kiowa historian. But it’s the stories of Davis's parents “Bus” and Vivian, both college-educated, artistic, creative and “knowledgeable about tribal culture” that truly shine a light on Davis’ upbringing.

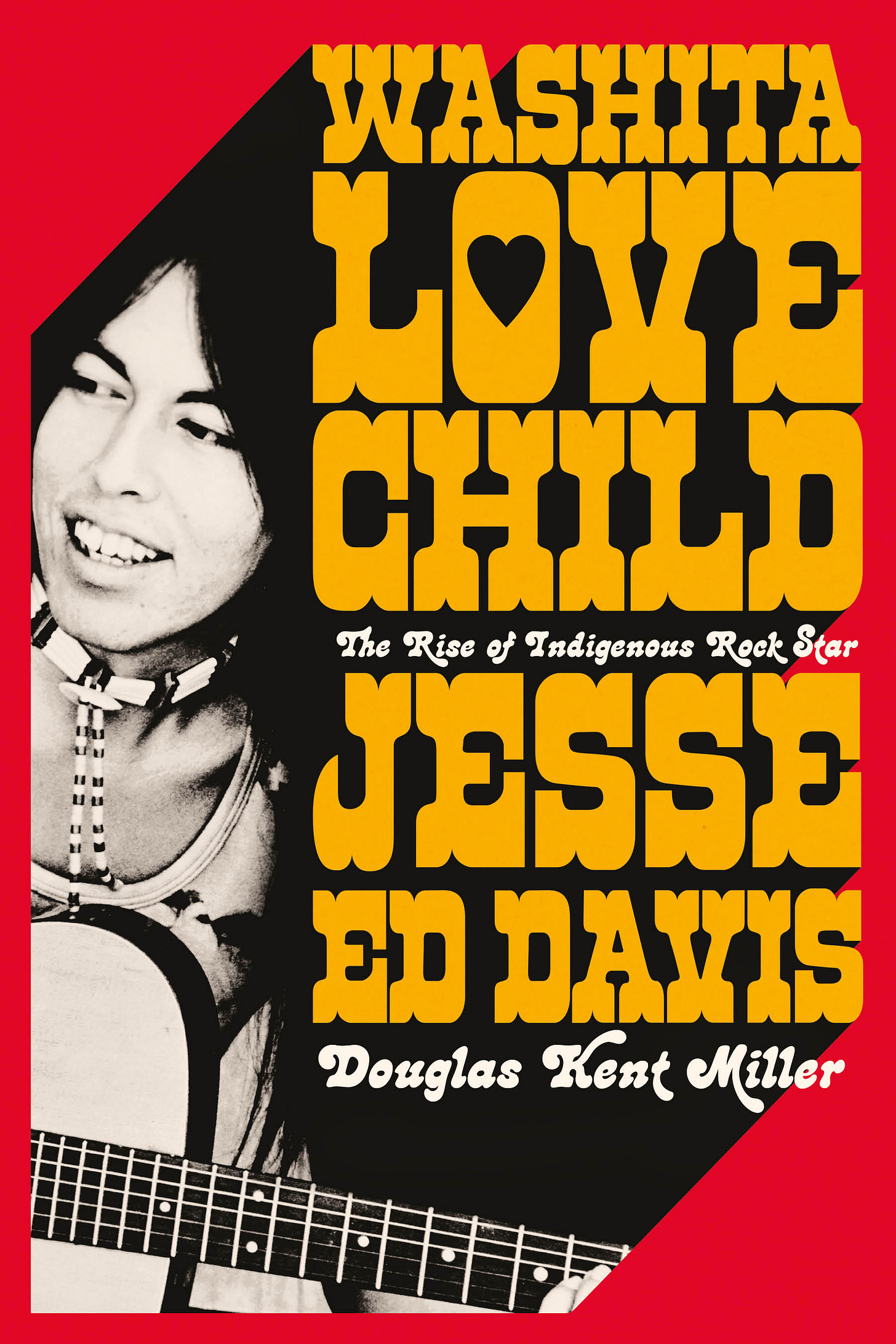

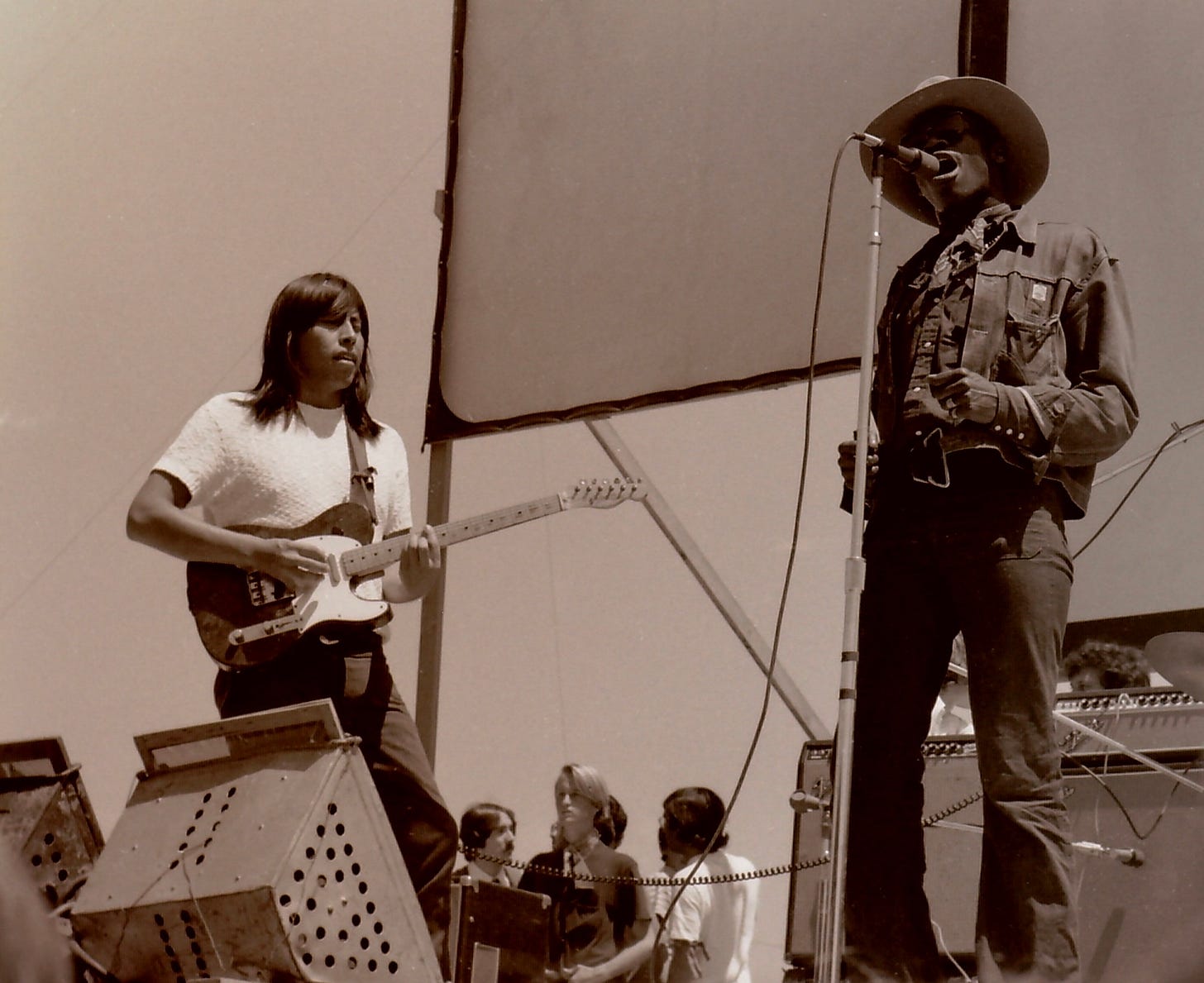

Jesse Ed Davis plays slide guitar at Santa Monica City College Amphitheater in 1973.

Photo: Howard Tsukamoto

He lived an upper-middle-class life and enjoyed support from his parents and the encouragement to seek out live music growing up in Oklahoma City. His most memorable concert was seeing Elvis at the OKC Municipal Auditorium in April 1956. Davis recalled later, “I wanted to be Elvis Presley so bad.” Although it took a while to put down the instruments that his parents had wanted him to train with — piano and the violin — he was granted a guitar and began the hours spent practicing in front of a mirror and taking lessons at local shop Jenkins Music.

Yet it was his grandfather Jasper’s death in 1959 that finally pushed the young Davis into the guitar as a means of self-expression. In that year of spirit mourning at age 17, the guitar was, as he prophesized “all I lived for.”

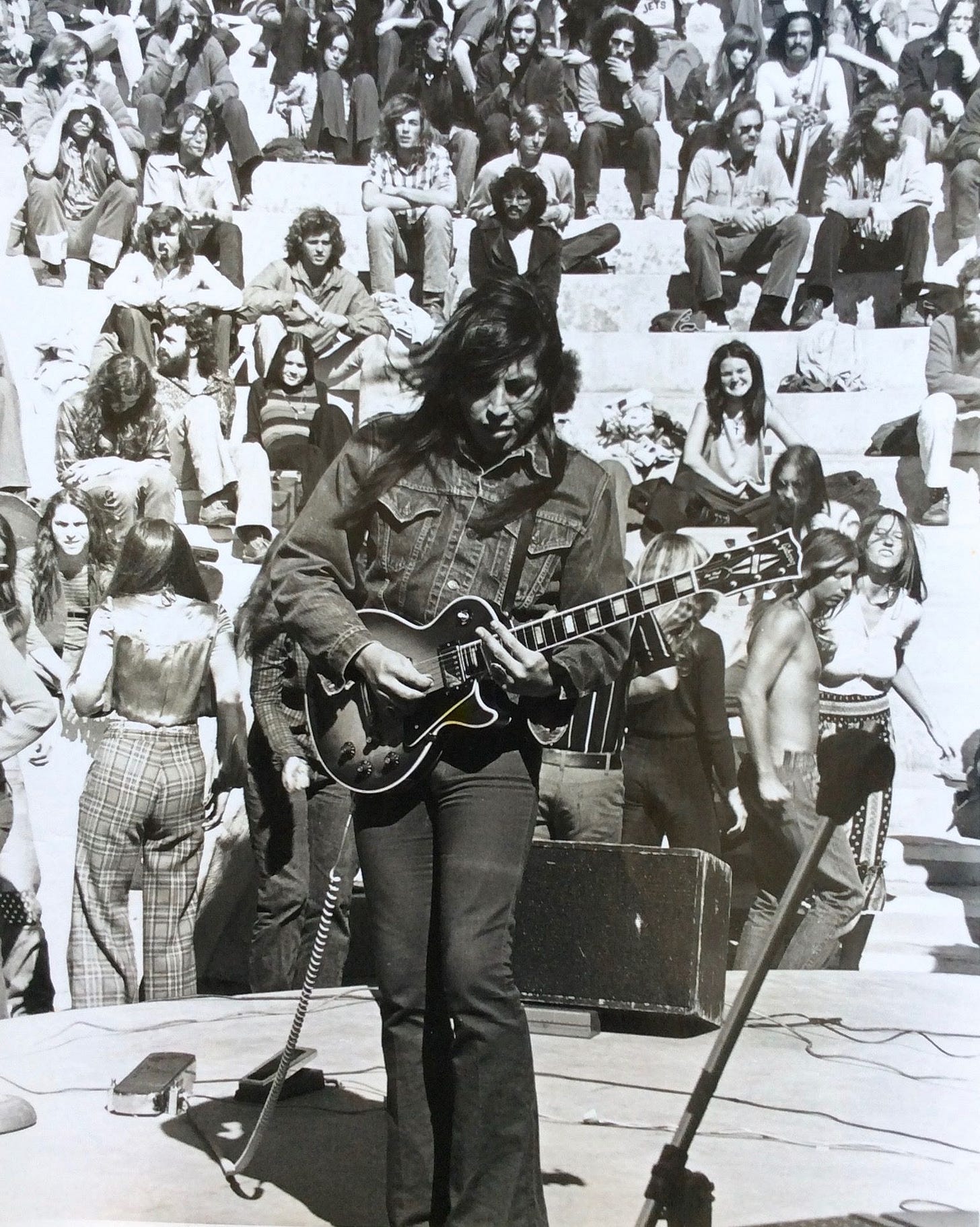

In high school, he excelled in sports and music, which author Miller classifies as a typical “overachiever.” Sometimes there was bullying, sometimes he resorted to a visual guard, pulling out a machete from under the driver’s seat of his car. It was all in the defense mechanism he had set up as someone who operated outside the system.

Northeast High School, Oklahoma City, 1962. Courtesy of the author.

Davis slotted into his first band, the racially diverse group The Continentals right after graduation in 1962, expanding and contracting to accommodate members and genres. They drove all the way to Fayetteville, Arkansas to Ronnie Hawkins Rockwood Supper Club to bask in the glow of the pre-Band The Hawks and superstars like Conway Twitty. And through that thread, Davis was able to stand next to Twitty as his guitarist, debuting on August 30, 1963, at Springlake Amusement Park, a venue that sat next to Davis’ house and where he had watched Twitty from the audience only a few years previous.

One continuous strand that runs through the book, are the tales that surround Davis’ life. Some are bound up in his own scattered retellings throughout his career. Miller surmises it was not a lack of focus, but more than likely casting aside the mundane and granular everyday. The events that shaped Davis eventually propelled him to move on to California in late 1966, moving into a communal Okie home, greeted there by Tulsa native Leon Russell. The combination of country, rock, gospel, and jazz certainly sounded real, but was that where the newly self-anointed “Jesse” Ed Davis fit in? He found out in 1967, courtesy of blues singer Taj Mahal.

“Agent and Captain.” Davis and Taj Mahal onstage, circa 1969. Courtesy of the author.

The interracial stereotypes called out by the press and the public within Mahal’s “Great Plains Boogie Band,” were not always acceptable to the mainstream, including the executives at Columbia Records where Davis was an integral part of a four-album release in those years. Davis also became a father-by-proxy in 1967 when he took up with Californian Patti Daley and her son Billy from a former marriage and Davis took to Billy, embracing him as his own. As Miller asks, with such a life as Davis had, could it get any better?

The future was held in the hands of Britian’s second most famous band. After invites to perform in London on The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus came in, the group including Davis, proceeded to rip the show apart. Backstage, as Davis picked some licks on “Mystery Train,” John Lennon (who had performed with Keith Richards, Mitch Mitchell and Eric Clapton) walked over, wordlessly grabbed a guitar, and formed a bond that day in December 1968 that would reverberate in years to come.

And the actual filmed performance that should have catapulted Taj Mahal and the Great Plains Boogie Band to stardom? Due to the inferior performance of the Stones and in particular Brian Jones, the entire show was shelved until 1996 – eight years after Davis’ death.

Taj Mahal, Homer Banks — Ain't That A Lot Of Love (Official Video) [4K]/© ABKCOVEVO/YouTube

Disappointment over the lack of label support and life commitments saw Davis move on in various instances, some life-changing for others rather than himself. Duane Allman learned slide guitar from listening to Davis’s “Statesboro Blues.” The Cars’ Elliot Easton was enraptured with Davis during his teenage years as was session guitarist Danny Kortchmar. However, Davis got in his first solo album, 1971’s ¡Jesse Davis!, a not altogether satisfying event, even with the support of Eric Clapton and Russell and the autobiographical “Washita Love Child.”

The Davis family moved to Venice, California, ensconced in a beachfront property that became known as Hurricane House, with a transient and carnival-like atmosphere that welcomed musicians traveling through the area. As his son later commented very accurately, “I just remember a lot of music. A lot of musicians. Music was the focus of the Hurricane House.”

Davis was able to turn his associations within the industry into star-studded gigs, including his invite to play at The Concert for Bangladesh in August 1971, albeit as a last-minute stand-in for Eric Clapton. Although sick beyond reprieve, Clapton eventually made it onstage, but it was Davis who shone that day. That type of star turn, however, didn’t translate to any further solo acclaim, despite the casting of stellar musicians like Jim Keltner (who played with Davis more than any other musician), Dr. John, and Beatle associate Klaus Voormann.

But the two parallel lives of Davis were beginning to intermingle and not for the better. While his distinctive one-take work could be heard on Browne’s “Doctor My Eyes” single throughout the spring of 1972 with his guitar playing in demand, to the point that he wasn’t merely deemed a “session” man — his ethic and proclivity for gelling in the studio placed him in the elite class of Los Angeles players who were called upon for their professionalism and prized for a sound that just no one could replicate.

He worked with Dylan, Arlo Guthrie, Steve Miller, Albert Collins, and B.B. King. But increasingly, his drug and alcohol use transferred to erratic behavior and questionable choices, as depicted by the cover art for his 1973 album Keep Me Comin’ with its sexually explicit collage of Penthouse centerfolds. His growing dependency on drugs was proving a liability.

Conditions collided when Lennon arrived in Los Angeles in late 1973, banished from his home by Yoko Ono, however looking for a creative vibe on the West Coast. Times had changed since 1968 and with Davis, the disruptive and turbulent atmosphere in recording Lennon’s Rock ‘n’ Roll and evening drinking sessions ended in catastrophe. The most violent and memorable was a complete trashing of Lennon’s rental home, with Davis getting klonked on the head, resulting in an appearance from the LAPD, but thankfully with no arrests.

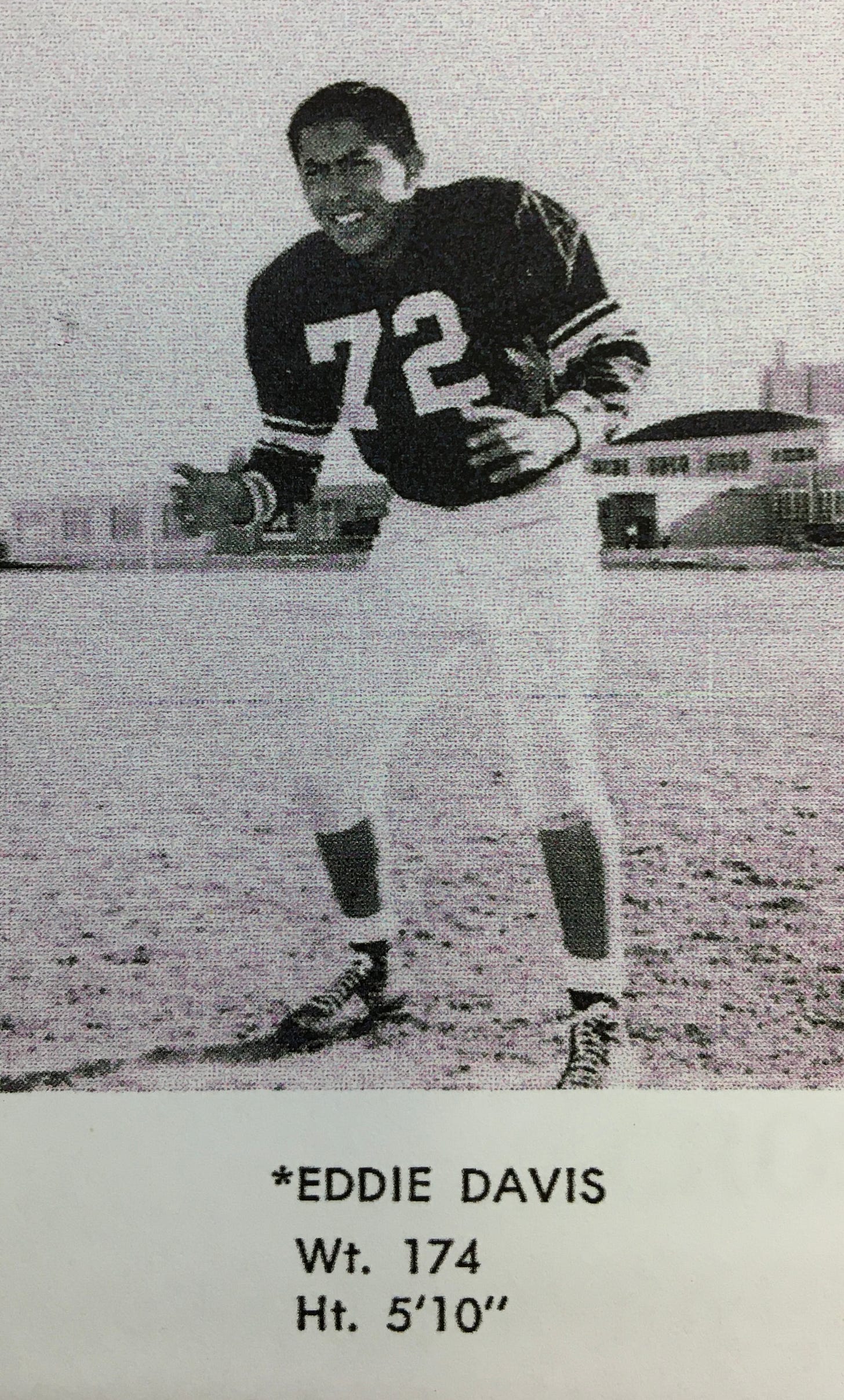

Bobby Daniels, Ronnie Wood, and Rod Stewart with Davis, backstage, circa 1975.

Photo: Patti Daley, Patti Daley Collection.

Where would all the shenanigans lead? After Lennon traveled back to the East Coast, he retained Davis for the Walls and Bridges sessions, pushing everyone like a “slavedriver” (Davis's term) in fear of a possible deportation. The guitarist’s work on those tracks, including his transcendent playing on “#9 Dream” remains to this day some of his most beloved accomplishments put to vinyl.

Burnt out on session work, he accepted an invite to play in the Faces, albeit with tensions mounting between Stewart (going solo) and Ronnie Wood (considered a front-runner to join The Stones). However, life on the road pulled too far for all concerned and as the demise of the Faces descended, so too did Davis’s relationship with his partner and son. This set of circumstances had Davis back in California, selling his guitars to score alcohol and heroin, even as his seductive licks on Stewart’s “Tonight’s the Night” wafted from the AM airwaves in 1976.

Rod Stewart — Tonight’s The Night (Gonna Be Alright) (Official Video)/℗©EMI April Music Inc./YouTube

His father died in 1977 during a recording session with Dylan and Leonard Cohen. Nonetheless, he found his way to Hawaii where Daley had stayed to escape the Hollywood madness as Billy had left to live with his biological father on the mainland. Davis mentored musicians and stayed sober. But for all that, his partnership ended with Daley, who unable to keep him clean, introduced him to Tantalayo Saenz, a wandering spirit that just might help him overcome his demons. They married in August 1980 in Oklahoma City.

In a long epilogue by Miller, Jim Keltner surmises that Davis died figuratively the same night as Lennon did on December 8, 1980. “I have a feeling he gave up,” was the drummer’s thought. Miller also posits that Davis regretted having spoken to Albert Goldman for his controversial biography of Lennon, sensing he may have given the author less than the truth for a good story. And not surprisingly, Miller also acknowledges that Davis's life in the ‘80s is difficult to track, due to illness, relocations, and numerous periods away from the public eye.

He would continually upend his life for money, begging for loans, pawning equipment, or a promise of a huge money-making gig. He reconnected with Billy and was guaranteed a tour with Clapton if he could stay sober. He couldn’t — letting down the boy who was enamored of his lifestyle and himself in the process.

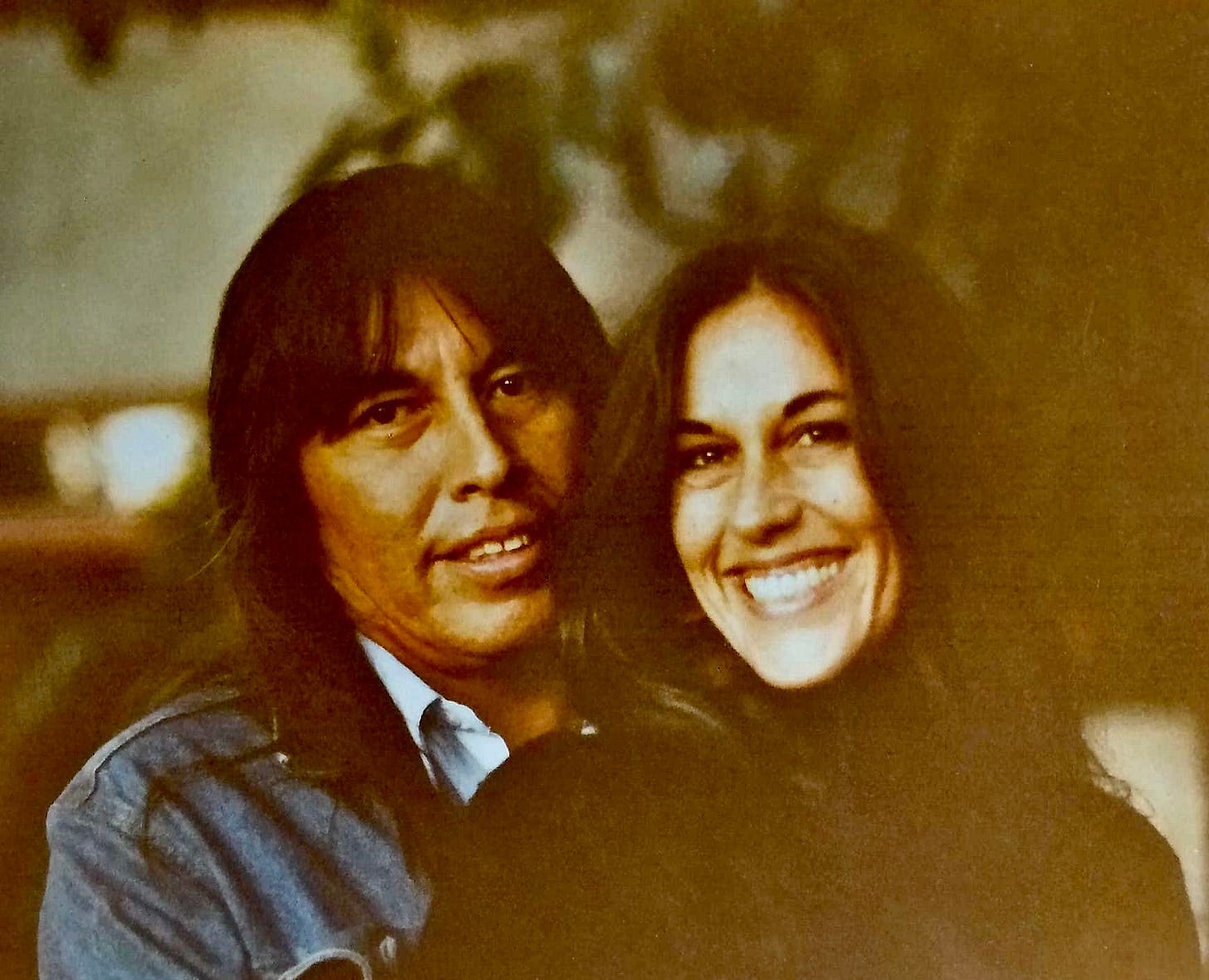

Jesse and Kelly Brady. Photo courtesy of Dave Tahchawwickah.

His last serious relationship led to a second marriage with Kelly Brady and a horizon that hopefully hinged on sobriety. She helped him into a rehab program in 1984 and from there he began a fruitful partnership with artist and Native American activist John Trudell as AKA Graffiti Man and were endorsed by Dylan in a 1986 Rolling Stone interview. This led to one of Davis’ final recording sessions in March 1987 where he worked with Dylan on a selection of covers that remain unreleased.

❧

Davis’ passing on June 22, 1988 is swathed in the blanket of loneliness, addiction and everyday life. Found on the floor of a laundry room at an apartment complex he had been to several times for a fix, his death — a needle mark on his arm, with heroin, alcohol, and the withdrawal drug Librium in his system — can be taken as tragic or foregone. Above all, he was blessed as so few could see back then and now as author Miller notes:

The music business can be tough on young artists. Not only was Jess not immune, he was a little more vulnerable. But when he played his guitar, he could make people change direction. Jesse Ed Davis won that battle.

Washita Love Child: The Rise of Indigenous Rock Star Jesse Ed Davis by Douglas Kent Miller, with a foreword from poet laureate Joy Harjo is available from Liveright/Norton and Bookshop.org. The author also includes a passage Davis wrote on Jimi Hendrix, fan letters regarding AKA Grafitti Man, a mixtape list from Davis to Daley, and a complete discography.

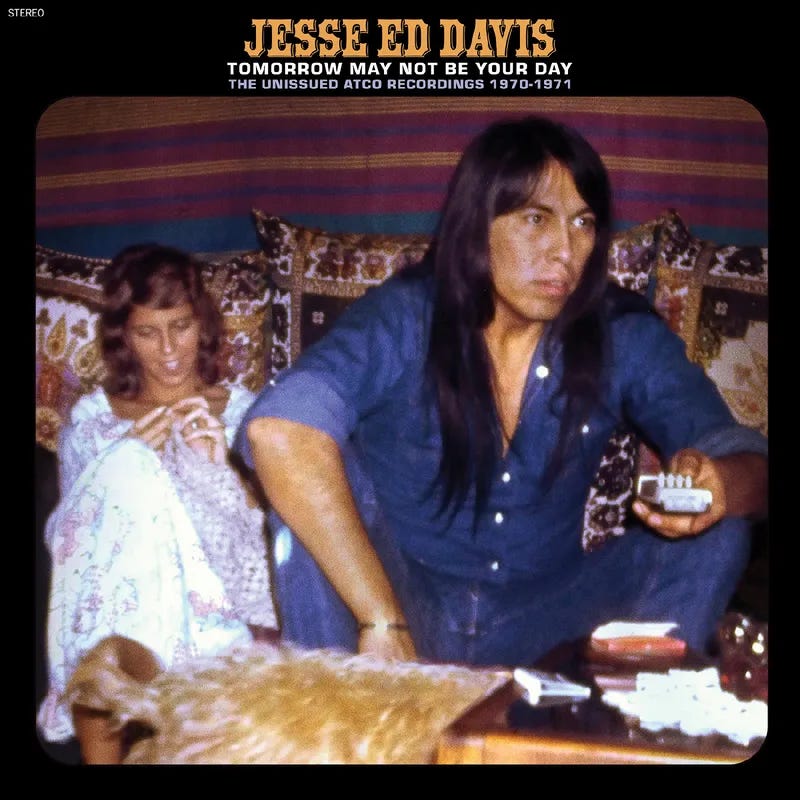

Real Gone Music released Tomorrow May Not Be Your Day: The Unissued Atco Recordings 1970-1971, a double-LP collection consisting of all unreleased recordings taken from Davis’s sessions for his two Atco solo records on November 29. With notes from Douglas Miller, the details on where you can purchase this limited edition vinyl pressing of 1000 can be found on the Record Store Day website here.

Thank you for introducing me to Jesse Ed Davis. I didn't know most of this.

I too think Walls and Bridges is underrated (as is Mind Games, which I'm currently having a love affair with, esp Sean's new mixes)

Also, there's a fair amount of evidence that Yoko didn't kick John out, that he left on his own and they ret-conned the story afterwards (and really none other than their unreliable narrator say-so that it was the other way around) -- the cover of Mind Games being one clue.

PS Happy Whatever You Celebrate!