Book Review – 'The McCartney Legacy: Volume 2 | 1974–80

Second in the series from McCartney historians Allan Kozinn & Adrian Sinclair

If you’re new to the McCartney series by authors Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair, please feel free to read my review of their first book, The McCartney Legacy, Volume 1 1969–73. [Note: this article and any before September 2023 are free to paid subscribers].

In The McCartney Legacy: Volume 2 | 1974–80, Kozinn and Sinclair brilliantly draw upon decades of information to flesh out the picture of an artist pinned at the crossroads of success and future uncertainty. Band on the Run had seemingly righted the wrongs the critics had given over to McCartney since his self-titled debut in 1970. However, McCartney wanted a ‘band’ not on the run. At least one that would take form more harmoniously than the acrimony surrounding Henry McCullough and Denny Seiwell’s tenure and departure.

McCartney found a hopeful kernel during the 1974 sessions for his brother Mike’s album McGear. Scottish native Jimmy McCulloch, at the wee age of 20, was impressing the ex-Beatle with his instinctual and finely-tuned playing. As something of a prodigy, he was top of the list for Wings Mach II, while drummer Geoff Britton impressed McCartney with his improvisational techniques.

As with Volume 1, Kozinn and Sinclair bring a mixture of McCartney’s life happenings that spin into his musical career. They also point out fairly early on McCartney’s mercurial tendencies to ‘fix’ issues he perceives within artistic compositions, citing the production of Peggy Lee’s “Let’s Love,” a song gifted to her by the former Beatle, but driven off the rails early on by arranger Dave Grusin.

Let’s Love – Peggy Lee/℗© 1974 Atlantic Recording Corporation for the United States and WEA International for the world outside of the United States/YouTube

Curly Putman’s 133-acre ranch near Nashville would be home base in July while everyone found their footing. But while hopes were indeed high, McCulloch and Laine were overindulging in every way possible, which resulted in various spats of varying degrees, mostly emanating from McCulloch.

Decorated with tales of tension and family life, the authors bring together rehearsals and recordings , including clandestine recordings at Sound Shop, that culminate in the country-flavored “Sally G,” the rocking “Junior’s Farm,” and one McCartney’s dad had been inspired to compose “Walking in the Park With Eloise,” helped in no small part by a contribution from legendary guitarist Chet Atkins.

Back in England, the August and September 1974 rehearsals and recordings at EMI Studio Two (again being used as rehearsal time for chemistry observations) were videotaped and included the reggae inflections of “Proud Mother/Mum,” the jingle composed for bread makers Mother’s Pride, and recorded as The Whippets. The conclusion and conviction from the body of evidence produced was that Wings might be an actual band, even with the minor personality quirks of everyone involved.

Paul McCartney – Proud Mum 1974/℗©MPL Communications Inc./YouTube

After the release of “Junior’s Farm” in November, it would have been a given that an entire album was needed to get the group ready for a tour. Those sessions continued off and on, as McCartney finalized recording time in New Orleans for 1975. John Lennon had expressed interest in swinging down there now that the papers had all been signed to dissolve The Beatles in December 1974. Prospects on that front seemed favorable, to say the least.

Wings and their roadies enjoy a Chinese takeaway at EMI Studios, November 11, 1974. Photo courtesy of Geoff Britton.

But mounting insecurities – Britton’s wife filing for divorce, his strict health regiment and karate disciplines at odds with the rest, and McCartney’s growing dissatisfaction with his drumming – were coming to a head. Waiting for McCulloch to join them in New Orleans and only three weeks into January, American drummer Joe English was flown in from Georgia, and Britton was hustled out.

“I just didn’t have any rapport with Jimmy and Denny,” said Britton. “Everybody got absolutely legless, on the knowledge that I would drive them all home, and I would be straight. I would have thought it was a blessing to have someone like me around, but it didn’t work out like that.”

English turned out to be exactly what McCartney was looking for, someone who came in blind and was able to adapt on the spot. He stayed on for the rest of the sessions. Conceptually, McCartney had the entire album, now known as Venus and Mars, all laid out. Everyone in the entourage went full force into Mardi Gras mode, but markedly without Lennon, who had reconciled with Ono.

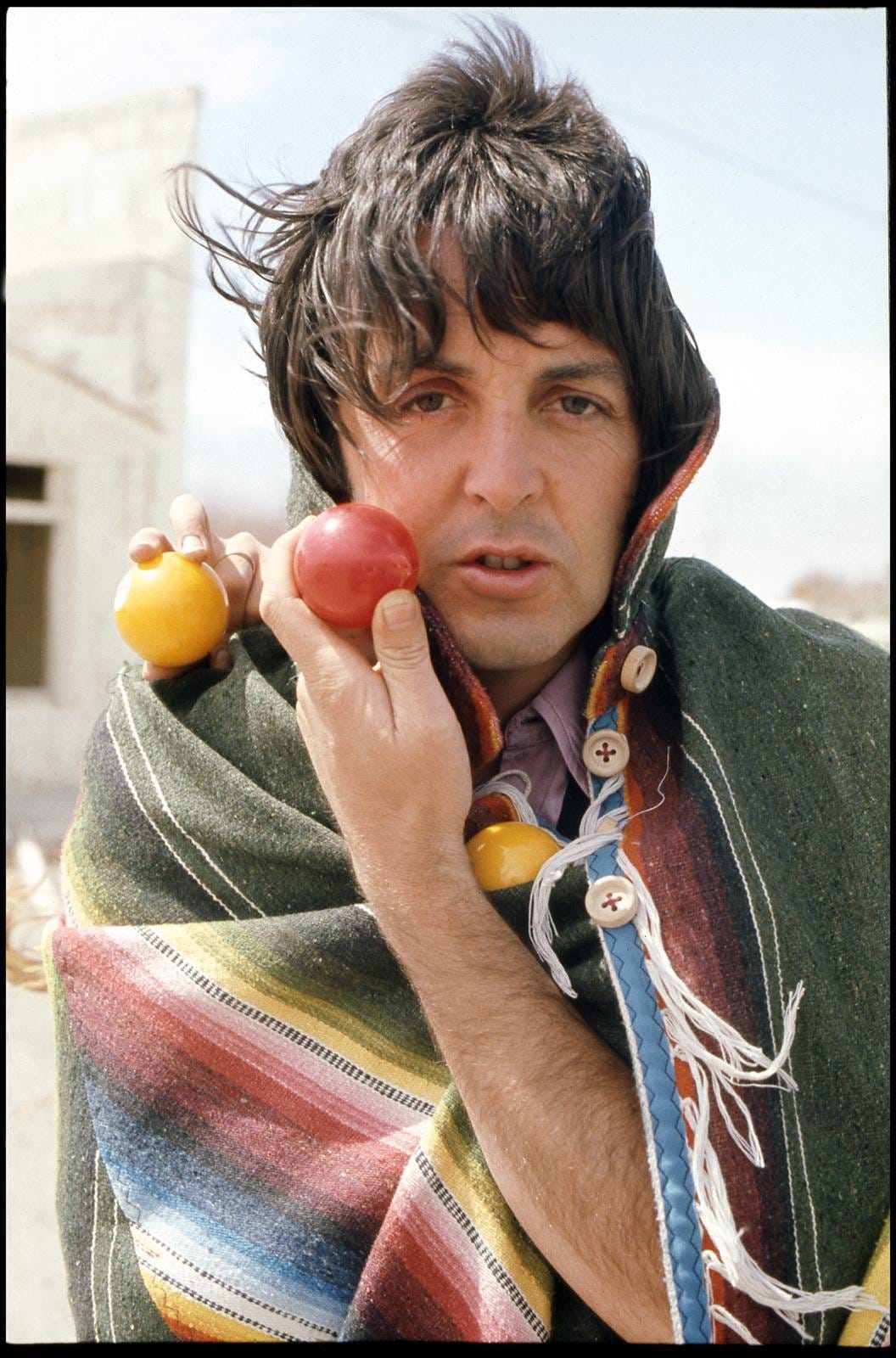

McCartney (with Linda’s hand) in the Mojave Desert for the Venus and Mars photoshoot. © MPL Communications, Ltd.

The McCartneys completed the album in Los Angeles, amid a marijuana drug bust for Linda (the family was pulled over for running a red light), but the real work was waiting to see the light of day in May. The first single “Listen to What the Man Said,” with a McCartney comic impersonation of Dr. John and improvised sax solo from Tom Scott, released May 31 and hit Number 1 in July. Venus and Mars was a favorite with the record-buying public, but the critics were mixed, and one unwilling to disguise their contempt for the sub-par fluff that McCartney had worked so hard to produce.

Admittedly, Linda was more than miffed at the criticisms of the press than her husband, as she noted at the time, “He likes positive thinking. Negative people get a bit on his back.” Having said that, there was no time to lie around. A tour was on the horizon, mapped and planned out for maximum punch. The lighting, sound, and professionalism they witnessed at a Led Zeppelin concert – only a decade on from The Beatles at Shea Stadium – impressed the couple that this was where they needed Wings to be, presentation-wise.

The British leg started on September 9, 1975. A preview three days earlier in front of invited guests, including Ringo and Elton John, had come across as too rigid and self-conscious, in McCartney’s eyes. But with material to cover from Wings, solo takes from Laine and McCulloch, and introducing English to the concertgoers, McCartney was fronting a united effort and he wanted to polish this band into a gleaming diamond for the road ahead.

The pure fact is that McCartney will have to live forever as an ex-Beatle, and yet here he was, on the Hammersmith stage, acting out a role that sought to kill off his past. By that yardstick, the show was just another rock band racing through some hot licks; yet we all knew things were different and nobody should judge it as just another rock band—if it was that, the theatre would not have been full.

Ray Coleman, Melody Maker

Kozinn and Sinclair recount a break in the UK tour with McCartney at his High Park farm writing and recording and later, landing in Australia in October for the next leg of the tour. Despite the best of intentions, though, Japan – the final stop of the tour – was canceled as that country’s minister of justice revoked visas for previous band members’ drug convictions.

The authors also recount the McCartneys’ New York City visit with the Lennons in December 1975 and the possible employment of Beatles’ roadie Mal Evans for the American leg of the Wings tour in 1976. The latter reveal is especially poignant given that Evans, having grown despondent of gainful agency coupled with severe depression, was killed by Los Angeles police gunfire on January 5 as Wings was recording “She’s My Baby” at the newly renamed Abbey Road Studios.

This specific studio time was at the behest of McCartney who had new material raring to go, knowing a European and US tour were on the horizon. However, the excitement was tempered by the death of Jim McCartney on March 18, as Paul was in the middle of a press party for the pre-release of the forthcoming tour and album. Choosing not to attend expecting to be surrounded by a media circus and as one who hid his grief privately, he forged ahead with the next chapter in his musical career.

Inner sleeve artwork for Wings at the Speed of Sound by Humphrey Ocean, with band photo by Robert Ellis/© MPL Communications, Ltd.

The bolder sounding, yet within trends of Wings at the Speed of Sound (inspired by a headline of the maiden voyage of the Concorde) was released on March 26 with no advance single. But of even more concern was McCulloch’s pinky finger. He and teen heartthrob David Cassidy, there by McCartney’s invitation, had gone on a Parisian bender at the last stop of the short European tour, when a drunken McCulloch smashed the TV in the former Partridge Family star’s hotel room, then fell over, breaking his left fifth digit.

A concocted story of McCulloch slipping on a bathroom floor was drawn up to spin away the debauchery for the month-long convalescence and finally with the drop on April 2 of “Silly Love Songs,” Wings were in the air and on the ground in America.

❦

At a New York City stopover before the beginning of the tour and encased in folklore since April 24, 1976 was the Lennon-McCartney get-together while watching Lorne Michaels offer the hysterically low sum of $3,000 for all four Beatles to reunite on Saturday Night Live. McCartney took each stop across America in stride, buoyed by the enthusiasm from the audience enthusiasm and the album sales by Wings.

“I think a lot of people came to see Paul the Beatle, even though he’s dead and gone. But I feel sure they left the place tonight with Wings on their brains.”

McCartney and McCulloch, Wings Over America, 1976. Photo: Jim Summaria/CC BY-SA 3.0

The US tour was a small triumph to all concerned, even if the press continued to smother McCartney with Beatles reunion questions. English was fairly homesick most of the time, as McCulloch kept up his drinking, coming to physical blows backstage in Boston with his boss, only to be held off by horn players Howie Casey and Tony Dorsey. His dissatisfaction with being a McCartney sideman and overindulgence in alcohol and drugs only fueled his insecurities – and being of slight build didn’t help matters or his metabolism.

The band reconvened for a short list of European dates in September, with one in Venice arranged to help UNESCO in its efforts to save the crumbling infrastructure along the famed canals. Coming home, work began on the "abnormal” amount of overdubs and fixings needed to get a live album out and the end of tour dates agreed upon would close out at the Empire Pool in Wembley in late October.

The triumph of completing the Wings Over America 3LP set in time for Christmas proved fruitful for all considered and its nabbing a Number 1 on January 22, 1977 on the US Billboard 200 was a giant step up for Wings as a collective.

'Maybe I'm Amazed' (from 'Rockshow') - Paul McCartney And Wings/℗© MPL Communications, Ltd./YouTube

The big news coming in for 1977 was that Linda was pregnant. But with the weather in London viewed as a dampening downer, the proposal to reinvigorate was supplemented by recording sessions aboard a reconfigured 105-foot yacht – the Fair Carol – moored off the US Virgin Islands, which proved irresistible and at times, frustrating. The band and crew stayed offshore until May 28 and were back in the UK by the beginning of June.

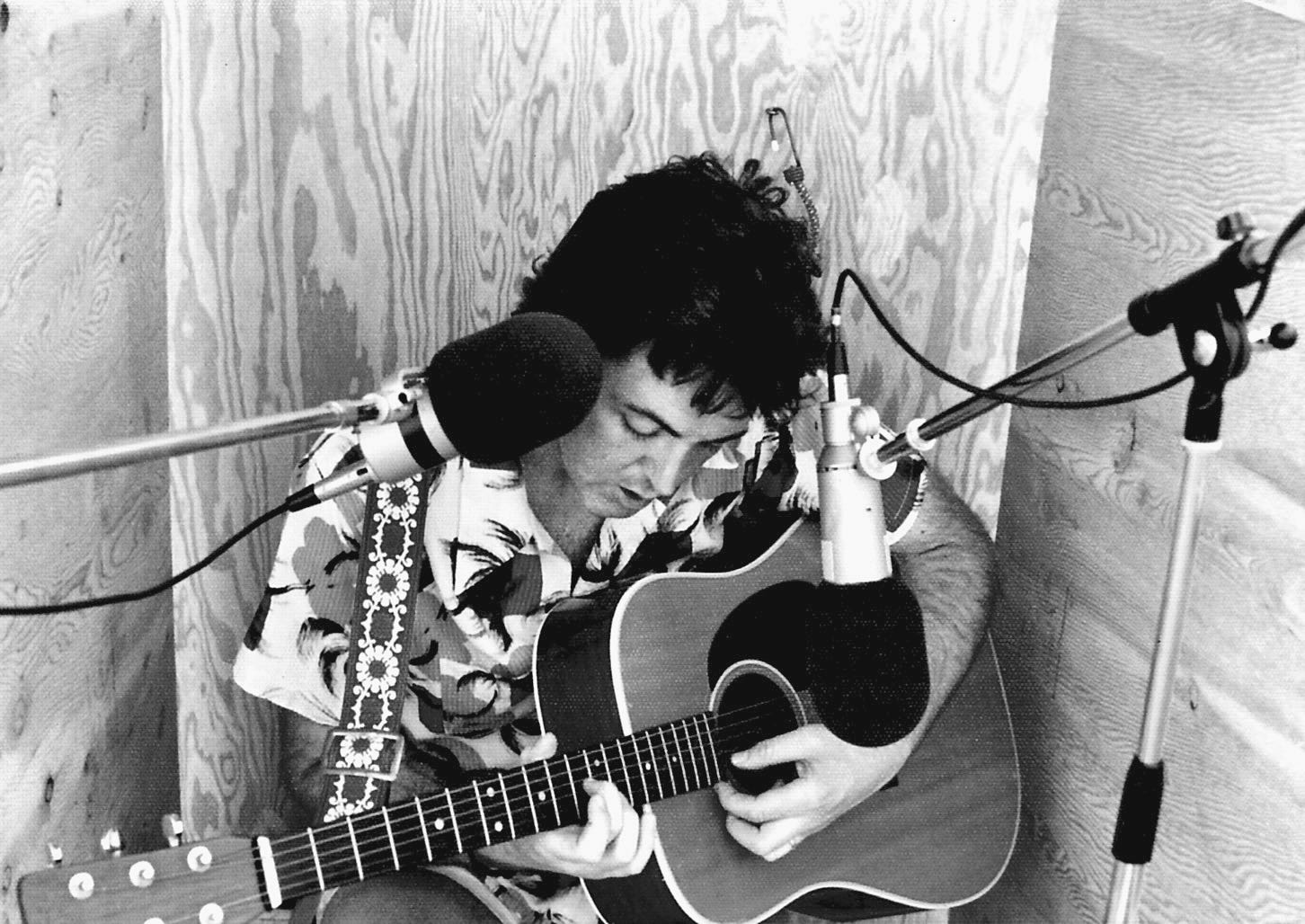

Paul tracks “I’m Carrying” on the top deck of the Fair Carol, May 5, 1977. Photo: Tom Anderson

Mid-July saw the birth of a song that McCartney had been holding onto since 1974. With Laine up in High Park on the farm, the two finished “Mull of Kintyre,” an ode to the Scottish surroundings and the family homestead. As for a proper studio he could rely on, McCartney summoned up his design team who had revamped London’s 1 Soho Square into MPL, and gave them a cow barn to makeover. In a month.

The newly named Spirit of Ranachan Studio was able to play host for the “Mull of Kintyre” sessions, squeaking by with a mobile studio for recording. But it was during the morning of August 9, that the finality of McCulloch’s time with Wings transpired. Bored with not much to do, he came back from a drinking session in nearby Campbeltown, trashed the cottage he was staying at onsite, and was promptly served his walking papers, courtesy of McCartney.

“What’s the use of having a brilliant guitarist in the band when he’s such an unpleasant pain in the ass who makes the whole thing so uncomfortable for you? With Jimmy he felt I was directing him too much. He’d never say, ‘No, I want to do it this way.’ I could just feel the tension rise. If he’d stayed, recording the next LP would have had problems.”

MPL created a diplomatic news release on McCulloch’s exit, allowing him to join a re-formed Small Faces, couched with the brightest delivery of the birth of James Louis McCartney on September 12. The news however was tempered with the word from English that while he admired McCartney and his music, he couldn’t carry on in Wings. His wife Dayle had been involved in a serious car crash before the sessions in the Virgin Islands and combined with his heavy reliance on hard drugs to cope with stress, English felt it best to stay home in Georgia and move on to something less stressful.

❦

Michael Lindsay-Hogg had come up to High Park in October to direct a laid-back music video for “Mull of Kintyre,” which was readying release. Yet in an amusing anecdote related by Kozinn and Sinclair, McCartney acknowledged the punk scene by way of his daughter Heather’s musical likes, but remained dedicated that a love song to his adopted homeland would be more favored than the single’s other/double A-side, “Girls’ School,” an in-joke strewn hard rocker, that referenced porn flicks.

Filming at Saddell Bay with the Campbeltown Pipe Band, October 13, 1977. Photo © Jim Miller

“Mull of Kintyre” with the 14-piece strong Campbeltown Pipe Band recorded at the new studio, was released on November 11. Taking a critical lashing in the music press and received with mild trepidation by radio, nonetheless, the record-buying public ate the single up in droves, making it the Number 1 Christmas single, spending nine weeks at the top of the UK Official Charts.

With the now-titled London Town ready for release in March and McCartney in the studio whipping up his bass-playing on a demo of “Goodnight Tonight,” a chance meeting with Laine and guitarist Laurence Juber at London’s AIR Studios and a Laine acquaintance introducing him to drummer Steve Holley were the tentative threads that would be woven into making Wings Mach 3.

The ‘unofficial official’ unveiling of Wings with Holley and Juber was an overdubbing/mixing session for the McCartney-penned “Same Time, Next Year” for the Alan Alda and Ellen Burstyn movie in April, which ultimately was never used. In its place, McCartney enlisted director Keith McMillan to film a promo for “I’ve Had Enough,” utilizing him to great impact and cementing a bond that would see ‘Keef’ work with McCartney to memorable effect later on.

Paul McCartney & Wings - I've Had Enough (Official Music Video, Remastered)/℗© MPL Communications, Ltd.

Having this video in the can was important enough that McCartney wanted to move on with Holley and Juber as an in-service band intent on putting together an album. Both moved into the renovated barn at High Park in June 1978 to begin work on new material with McCartney ally and producer Chris Thomas in the passenger seat acting as a sounding board.

The ethos of punk during the recording sessions was not lost on Thomas, who had tried to work his magic with the volatility of The Sex Pistols. It didn’t help matters that McCartney was flying in many directions at this time: bringing back songs for a Rupert the Bear film, collaborating on a sci-fi movie vehicle for Wings, while having a bash on a quickly-formed piece of punk “Spin It On,” in addition to the quasi-Baroque “Winter Rose/Love Awake.”

“Love Awake” orchestral overdub session, April 1979. © Adrian Sinclair

One voice that made a crucial decision was Heather McCartney, Linda’s daughter from her first marriage. Juxtaposed against her teen years in London, Heather’s remarks to Paul put in motion the finale to move from Scotland to Peasmarsh near the south coast of England. The rural community was away from the prying eyes and harsh perspective of the ‘rich kids’ mouthiness towards Heather, which suited McCartney just fine: “Realizing that she was mixing with children who had this mentality was very worrying. It was the thing that sparked off this whole change for me.”

Recording continued in September at Lympne Castle in Kent, under the moniker ‘The Electricians’ and the castle’s proprietors Harold and Deirdre Margary recorded spoken-word passages for the track “The Broadcast.” The band also recorded demos for what ended up being the (future) Grammy-winning “Rockestra Theme” and “So Glad to See You Here.” The final sessions were moved to Studio Two at Abbey Road Studios in October to accommodate the massive amount of musicians invited and the mammoth sound they created, if only for it being largely instrumental, except for the improvised “Why didn’t I have any dinner?” line, originally put in as a horn section placeholder.

Paul McCartney & Wings – Rockestra Theme/℗© MPL Communications, Ltd./YouTube

Wings Greatest placated Capitol Records for a holiday release with its infamous cover shot on top of Brienzer Rothorn in the Swiss Alps with the McCartney’s Semiramis sculpture as its focus. The entrance to 1979 was still on Wings to make Holley and Juber public-facing, most notably with “Daytime Nighttime Suffering,” a weekend writing exercise from McCartney recorded with baby James crying in the background and finishing up “Goodnight Tonight” with Juber’s flamenco-inflected guitar riffs. This was the debut of McCartney’s new record deal with Columbia, released on March 23, as non-album tracks to the forthcoming Back to the Egg.

Winding up for that album’s release, McCartney dropped two different singles – for the UK, “Old Siam, Sir” and for the US “Getting Closer” – both ending marginally in sales and consequently, not the best news for his new label. The album’s release on June 8 was heavily criticized (in hindsight, unsurprisingly) in the British music press:

“There are no messages in these songs, no evidence of urgent need to put the world to rights through the power of rock ’n’ roll.”

“[He] seems to be on a treadmill of banality.”

“Just about the sorriest grab bag of dreck in recent memory.”

One curious outlier example of this kind of copy was sending Holley and Juber to the US for press, as McCartney hung back, building a studio at his East Sussex property to begin experimentations on his own. He was intent on exploring ideas and sounds that might not have a proper place within Wings, with “Front Parlour” and “Frozen Jap” as the first compositions. Kozinn and Sinclair also spring a surprising factoid: on what McCartney defined as a “boiling hot day” in July, he came up with and recorded on his own “Wonderful Christmastime.”

❦

On September 27, as McCartney was mixing solo material at Abbey Road Studios, two miles south at the Maida Vale flat of Jimmy McCulloch, Metropolitan Police were trying to piece together the circumstances of his death, eventually leaving it as an open verdict with no clear cause except noting it as morphine poisoning. A few days later on October 4, Paul and Linda sent flowers and a tribute to read at his funeral.

“I saw his folks once, his uncle and dad showed up,” McCartney reflected later. “And it was a binge. It wasn’t just meeting his uncle and dad—it was, ‘Get the bottle out!’ I guess he just grew up in that kind of thing. It isn’t easy for some people to cope with that.”

While not precisely at that moment, the back of mind thinking acknowledged in private, was that McCartney was getting tired of fronting a band. The authors rightly surmise that by October 1979, McCartney had seen enough implosions of his band; that the thought of going out as ‘Paul McCartney, the frontman of Wings,’ was filling him with trepidation and dread. Due to go out on tour in November, Wings had not even brought together a setlist, let alone had any rehearsal time on the books.

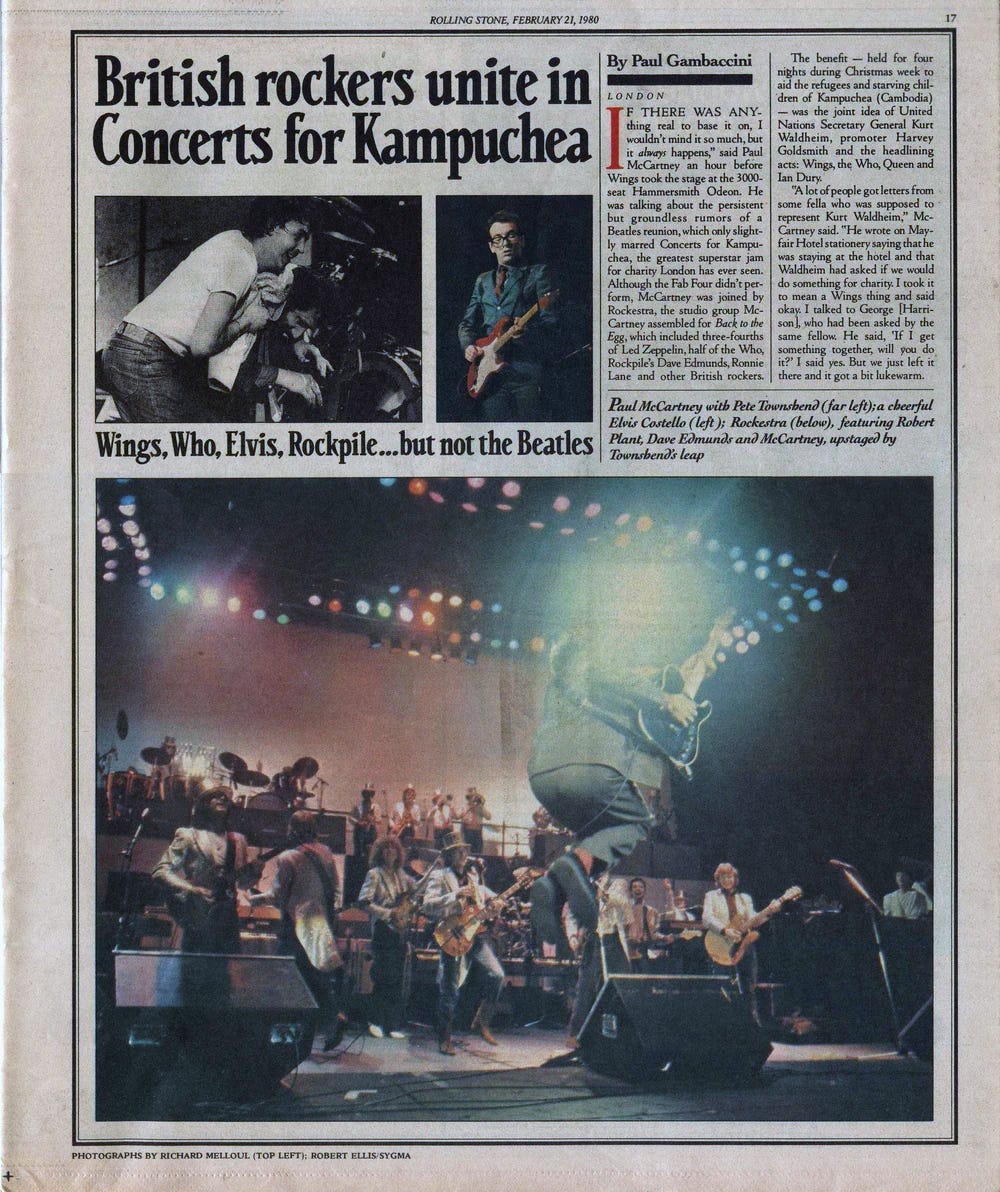

But, as was his nature, McCartney pulled it together and threw himself in full force. Less focus was placed on a killer light show and more on a tight rock and roll concert. The tour would start off in Liverpool on November 23 and wind its way around to the Apollo in Glasgow on December 17. Promoter Harvey Goldsmith was also looking to work in a gig that UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim had sought as a benefit for Southeast Asian refugees and shift off rumors of another plea for a Beatles reunion.

Yet as the tour pushed through a rather bad winter, McCartney had found a small win: by working in smaller venues, gracefully acknowledging his past, and playing up new material, Wings seemed to satisfy a majority of the music press, at least outside London. With a small break at the last show in Glasgow, the finale for the charity, now called The Concerts for the People of Kampuchea, took place December 26 to the 29th at London’s Hammersmith Odeon.

Early January 1980 had Wings back in East Sussex, gearing up in rehearsals for the next leg of their tour in Japan. Starting on January 21 with gigs at the Nippon Budokan Hall in Tokyo (site of the infamous Beatles 1966 show), concerts at Aichi-Kien in Nagoya would follow on January 25 and 26, then Festival Hall in Osaka on January 28, and back for three final Budokan shows, January 31 through February 2. Since the announcement was made, 100,000 tickets had been sold.

The horn section – in place from the short UK tour – would be going over and the McCartneys met with Chris Thomas prior to leaving, as he would be joining them in Tokyo. He also gave a warning to Linda: under no circumstances should they try to smuggle in marijuana for recreational purposes. “It’s a different world,” he mentioned. “They’ll lock you up there and they’ll throw away the key. This is serious, you cannot do it this time.”

Various band and crew contingents made their way to Japan, with everyone in by January 16. Juber had come with the McCartney family to Narita International Airport and was next to Paul when the bassist’s last suitcase was inspected. Out came a small bag of weed. After Juber was let go, the rest of Customs brought the McCartney family into another room and found more stashes – 220 grams in total.

Led away in handcuffs by Japanese officials, McCartney was taken to the Ministry of Health and Welfare for questioning. He was assigned as Prisoner 22, locked alone in a holding cell at the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Detention Center, facing the possibility of seven years of incarceration. Holley noted later, “That was a very bad day.”

By evening, the tour was canceled and McCartney, unable to sleep on the 14-hour flight to Japan, was now sitting up against a wall “in the green suit I’d arrived in.”

“It was hell.”

The McCartney Legacy, Vol. 2 1974–80 by Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair is published by Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Great review - sounds like a fascinating book!

A great review. Really enjoyed reading it.